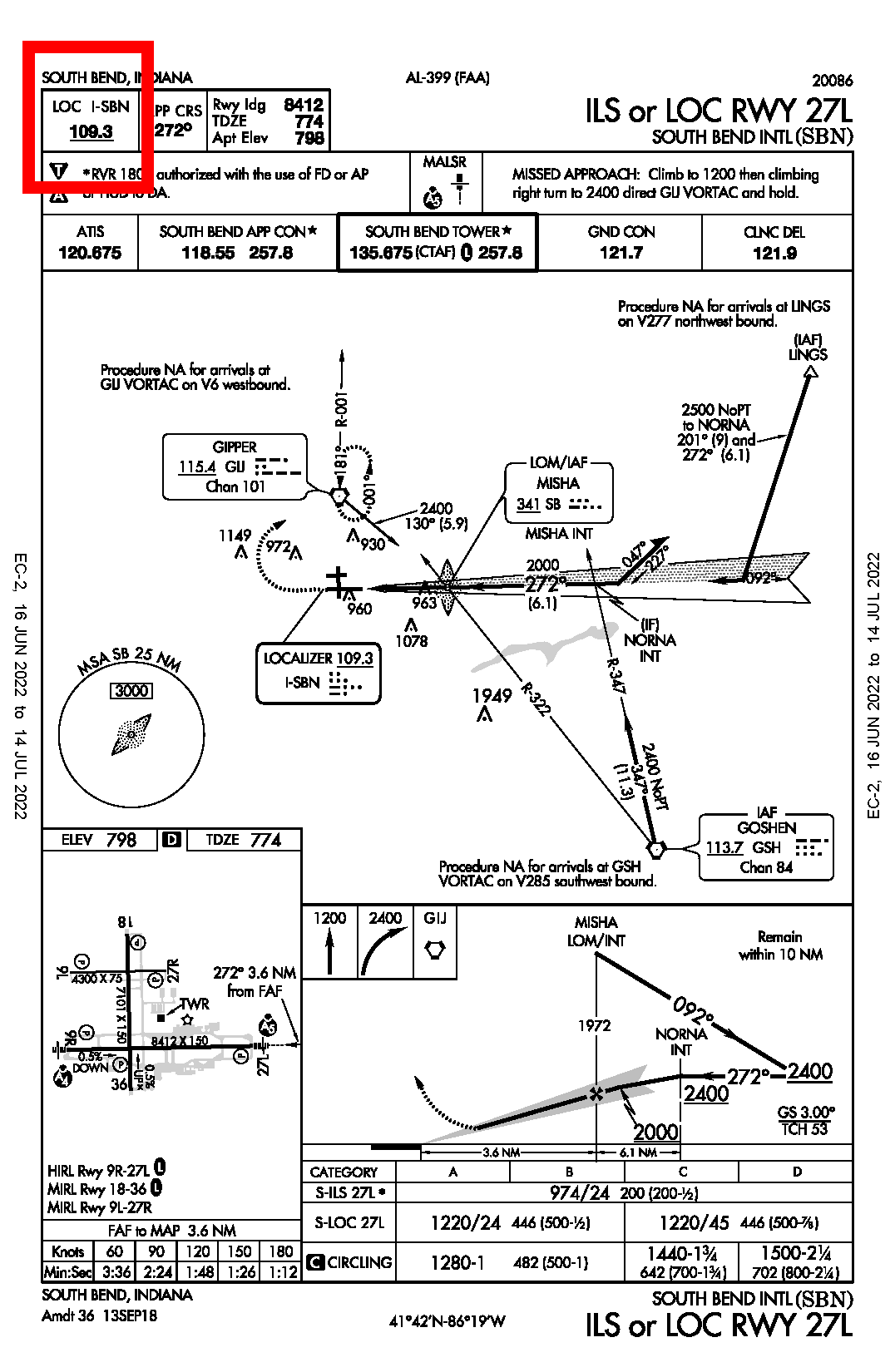

Not long ago I was on a flight during which we were setting up to fly an ILS approach at South Bend, IN (KSBN). The aircraft had a glass panel, a G1000 to be specific, and the approach was programmed into the system after selecting the airport and approach we desired.

But things weren’t going quite as they should normally.

There were hints to this effect however. Hints that a good instrument pilot or CFI-I should be taking into their scan and would cause them to ask some questions, namely, what the heck is wrong and am I going to be even able to continue this approach.

The first hint should have been when ATC gave the vector instruction, “turn right to 330 to intercept the localizer.”

The good news was that that vector was correct; the bad news was that it certainly didn’t match up with what the CDI was depicting.

This is where problem-solving needs to begin for a pilot in IFR conditions.

First, the pilot had the CDI selected to LOC2. While it might work, a best practice would have been to be on LOC1. The pilot had already tried that one and it wasn’t working, so had switched to LOC2 to see if it improved the situation. It didn’t.

I’ll admit, at this point, I also had a moment of confusion and was doing a little cross-checking to see what might be up. I noticed it pretty quickly.

But before I give away the punch-line, let’s talk bout some other cues that should lead a pilot in this case to recognize something is wrong.

Since we were only about 5 or so miles from the final approach fix, it also was a red flag that there was an indication of “NO GS”. This was telling us that there was no glide slope being received. The ILS certainly should have been giving a glide slope by this point even if we weren’t necessarily centered vertically on it.

Two major flags here and it was time to finish that cross-check.

Remember those three T’s we go through when setting up an approach?

Tune, Twist, Talk (Id).

Ok, so, tune.

Checking the approach plate, I saw that the proper localizer frequency was 109.3. Check, we had the right frequency tuned.

Twist. Yup, we had the correct inbound course twisted into the CDI. Good there also.

Talk (ID). ID’ing the correct signal identification is critical to making sure that we are on the correct navigation source.

And here is where the problem was identified.

We can see from the approach plate that the ILS for 27L should have an identification of “ISBN”, but if we go back up above and see what was actually being identified in the G1000 was “IUXW”.

And we have found our problem.

While we had properly set up the approach, the signal we were receiving wasn’t correct.

This is where a pilot must make a decision. In reality, there is only one decision to make here.

Go missed, abandon the approach, and go figure out what was wrong or find a different approach. Continuing the approach is either an indication the pilot is unaware of the problems, unable to identify there is a problem, or willing to continue when not properly receiving the approach information. Such a decision could easily lead to a catastrophic outcome.

We did find out what caused the discrepancy in this particular case. When the problem was identified, the approach was abandoned and ATC was queried.

“South Bend Tower, it appears we are not receiving the localizer correctly,” I notified them. “Are there new NOTAMs recently indicating a problem?” I asked. We had checked NOTAMs right before the flight and there weren’t any that were affecting the approach we were going to fly.

The response from ATC wasn’t what I had expected, but did give us our answer.

“Sorry, we forgot to switch the localizer over from runway 9R,” the indicated.

South Bend had been using runway 9R previously in the day, but as the winds switched, they switched their runway operations. When they did so, they had not switched the localizer that was turned on from 9R to 27L and it was the cause of our receiving the wrong indications and identification for the localizer.

In this case, we were just flying a practice approach in VFR conditions, so all was safe and well, if not exactly how we had expected to receive the approach signals for our practice.

If this were in actual IFR, it would have been critical that a pilot identified the discrepancy and made a safe decision; not proceeding with the approach.

While this was a bit of a fluke happenstance, it illustrates the potential that on any approach something might not go correct. It is why we check and cross-check our setup and what we are receiving. It is why we can’t get lazy and skip those verification steps in our IFR flying.

Make sure if you are getting a signal, that it is the correct one. Just getting a signal might not be enough to get you to the correct place at the end of an approach.

Stick with those fundamentals of checks, setup, and cross-checks you learned in your basic IFR training. They may just save your life sometime.