Diving and Flying – More Information about What Pilots and Divers Need to Know about Flying After Diving

Most pilots and divers know a minimum about when a diver can fly after diving as recommended by either the FAA or dive training agencies or professionals. But few really have gone any further than these basic recommendations to know more about why or how long they really need to wait to be safe to go flying. This consideration can be even more of a factor for pilots flying passengers who have been diving or divers who are flying in personal or chartered aircraft that operate outside the traditional parameters of commercial airline transport.

In both the pilot and diver communities, some initial training indicating that divers shouldn’t go flying right after scuba diving is present. While few learned any more than the basics, there is much more that needs to be known to fly safely after scuba diving.

Diving and flying are activities in which many people commonly engage in both. There seems to be a big overlap in the hobbies and a natural fit for the use of aviation to travel to diving destinations for vacation. This commingling of activities, when not planned for properly, can become physically dangerous and even fatal if not properly managed.

So, let’s imagine you are a corporate pilot flying a Piper Chieftain, a King Air, or a Leer Jet. Maybe you just got that first gig flying a privately owned Cirrus for a small company and the passenger (or your boss) asks to fly to a warm weather, beach based, location for a little trip. Or perhaps instead of being the pilot, you are someone who chartered an aircraft to take you and/or your family to a great destination for a mid-winter week long vacation. In each case, flying in a non-airline aircraft may require some additional information to be safely able to complete the flight after diving.

The topic isn’t one of just curiosity for the casual pilot, it is something that must be addressed according to practical test standards for multiple FAA airman certificates. Training on the aeromedical effects of scuba diving on pilots and passengers is specifically spelled out in private and commercial pilot testing standards and is a required item for testing. Yet a more in depth understanding of these effects is regularly missing in this training. If the pilot doesn’t happen to be a diver, or the diver isn’t somewhat knowledgeable about the flight environment of non-airline flights, there is a disconnect between the two industries that can lead to a potentially dangerous medical situation if a passenger flies too soon after diving.

Effects of Pressure – Not just hypoxia.

Pilots learn about hypoxia, focusing primarily on carbon monoxide or altitude based hypoxia symptoms. In a sense, the altitude based hypoxia symptoms are pressure based and relate to the change in altitude and oxygen density that pilots (and their passengers) experience as they climb in altitude above sea level. The same holds true for divers who go below the surface of the ocean. They experience the opposite, an increase in pressure as they descend at a rate of approximately 1 atmosphere per 33 feet (34 feet in fresh water) of descent. So a diver experiences approximately 4 atmospheres of pressure when diving to 100 feet of depth. It is this added pressure that affects the ratio of nitrogen to air that a diver experiences when diving. Without going into more detail, the greater the depth, the more nitrogen that a diver’s body absorbs. Time also makes a difference. More time at depth also means a diver gets more nitrogen in their body. A combination of time and depth determines how much nitrogen a diver’s body has absorbed. If a diver does not “off gas” this nitrogen either via time spent on the ground prior to flying, or if needed, using decompression procedures on their ascent from depth, they will experience what is commonly referred to as “the bends.” The primary way to off gas nitrogen is through decompression procedures (spending time at a variety of depths with an ascending procedure including stops at different depths during the ascent) and an interval of time spent on the surface that allows the diver’s body to release the nitrogen from their body.

When a passenger of an aircraft ascends to altitude, they decrease in pressure. While the decrease in pressure is not as significant when ascending in an aircraft as the increase in pressure is when descending underwater, a plane flying at 10,000 feet above sea level experiences approximately 70% of standard atmospheric pressure and oxygen content, a plane flying at 18,000 feet experiences approximately ½ of standard atmospheric pressure, and a plane that was fly at a common cruising altitude of a 30,000 would be experiencing ⅓ normal atmospheric pressure. (Want to see the math? Check out this altitude/pressure converting website at http://www.altitude.org/air_pressure.php)

Most commercial aircraft operate at cabin pressure altitudes of 8000 feet (approximately ¾ of standard atmospheric pressure) or lower to limit exposure to reduced atmospheric pressure and hypoxia due to lower oxygen levels at higher altitudes. This isn’t necessarily the case with all corporate or personal aircraft. Depending on the oxygen system in the aircraft, some pressurization systems do not keep the cabin pressure altitude that low and many aircraft do not have cabin pressurization. While some aircraft will offer oxygen masks that crew and passengers will use to avoid hypoxia symptoms while flying at higher altitudes, this would not be effective at avoiding the effects of lower pressure of flight at altitudes in non-pressurized aircraft.

The higher you go, the lower the pressure that is present. If a passenger or crew member had been diving, nitrogen is able to be released more easily. This results in greater effects of decompression illness (commonly called “the bends”).

What is “The Bends” – Symptoms a Pilot Should be Aware of for Passengers

“The Bends” is common terminology for the effects that divers will experience if they have ascended to the surface too quickly or traveled to an altitude (if flying) where the nitrogen in their body is no longer being released at a safe rate. When nitrogen is released too quickly from the body, it comes out of solution and forms gas bubbles in tissues and blood and can cause blockages that result in decompression sickness symptoms. These gas bubbles will cause numerous symptoms which commonly include skin rashes, irritable skin, breathing difficulty, joint and muscle pain, or even more dangerous symptoms like dizziness, vision limitations (blindness even), convulsions, or unconsciousness. The severity of the symptoms can vary, but in general terms, the deeper and longer a diver is underwater and the shorter the time period between their ascent to the surface and/or ascend to flying at higher altitudes, the more pronounced the symptoms are likely to be. They can be fatal.

Decompression illness, is what passengers or pilots who go flying after diving too soon are actually experiencing. A diver who may not otherwise feel any effects if they remain on the surface after diving, may cause decompression illness symptoms to form and be felt if they do go flying to higher altitudes too soon after completing one or multiple dives.

Pilots of passengers who have been diving recently, or divers who will be flying should have an awareness of these symptoms. Even symptoms that seem to be slight can become more pronounced and should be addressed immediately. For example, if a passenger is complaining of some achy joints, back pain, and maybe a little dizziness, these may be the first manifestations of symptoms that the individual is experiencing some decompression related symptoms. If on the ground, this would certainly be a reason to not take the passenger on a planned flight and get them to a local medical center. If they didn’t manifest themselves until in flight, it would be a reason for an immediate descent to lower pressure altitudes and diversion to an airport that could have a medical team waiting to receive the passenger.

Want to learn more about the technicalities of decompression illness, read Decompression Illness: What Is It and What Is The Treatment? by Dr. E.D. Thalmann, Divers Alert Network Assistant Medical Director.

Controlled Ascents – What they are and how they affect flight considerations

If you ask a diver, most will tell you they always make a controlled ascent. And in one sense, they do, but this is where the FAA terminology and terminology of scuba diving diverges a bit. A controlled ascent in the FAA terminology refers to a dive that requires decompression stops. Most divers will refer to this as a decompression dive, not a controlled ascent.

A decompression dive is one on which a diver has descended to a depth, or for a period of time, or a combination of both, that requires them to stop (maybe multiple times) on their way back to the surface to “decompress,” or let more nitrogen out of their body. While most recreational divers do not experience this type of diving, some do. A diver who has performed a “decompression” or “controlled ascent” dive has needed to adhere to special procedures to return to the surface of the water to avoid decompression sickness symptoms. These procedures are in place to allow a diver to safely return to the surface, but in no way guarantee that the individual is now able to fly in an aircraft to further reduced atmospheric pressures.

Decompression diving is less common for recreational divers, but as equipment has become more available, training more common, and divers seek to experience new challenges, more people are engaging in diving that requires decompression procedures.

Pilots or passengers who engage in this type of diving should know that these divers will require longer periods of time between their dives and flying. How much more time should be added you may ask? Well, let’s consider some industry recommendations as we think more about what is needed.

Industry Recommendations

The FAA’s Airman’s Information Manual (AIM), section 8-1-2 (d) offers a small section entitled “Decompression Sickness After Scuba Diving” that indicates “a pilot or passenger who intends to fly after scuba diving should allow the body sufficient time to rid itself of excess nitrogen absorbed during diving. If not, decompression sickness due to evolved gas can occur during exposure to low altitude and create a serious in-flight emergency.” But what does that really mean? How long of a wait is really required?

DiveCompare author Mike, notes that, “…the recommendation set out by PADI [the Professional Association of Diving Instructors] is: For single dives, a minimum preflight surface interval of at least 12 hours is recommended. For repetitive dives, or multiple days of diving a minimum preflight surface interval of at least 18 hours is recommended. DAN (Divers Alert Network) recommend 24 hours for repetitive dives, The US Air Force recommend 24 hours after any dive, while the US Navy tables recommend only 2 hours before flying to altitude.” (https://www.divecompare.com/blog/flying-diving/) The discrepancies in these agency recommendations and even the FAA AIM highlights the complexity of the question of how long someone needs to wait to fly after scuba diving.

The AIM tells us that a pilot should wait at least 12 hours prior to flying to altitudes up to 8,000’ (MSL) if a dive has not required a “controlled ascent” (non-decompression stop diving) and at least 24 hours after diving in which a “controlled ascent” (decompression requiring) is required. Any flight above 8000’ MSL should be delayed until at least 24 hours has elapsed. “These recommendations are actual flight altitudes above mean sea level (AMSL) and not pressurized cabin altitudes.” This is a critical point because it takes into account concern for any potential loss of pressurization in aircraft that operate in pressurized cabins. In other words, the cabin pressure altitude should not be the measure, the actual MSL altitude at which a flight will be considered is required to be considered for safe operation.

Waiting is the Best Way to Minimize the Effects of Diving Maladies on Passengers or Pilots

Avoidance of activities that would result in increased risk of pressure related sickness after diving is the best course of action. Spacing any flying further in time from the last dive is the best method. The more time between a dive (of any depth, but certainly longer for deeper or longer dives) and a flight the safer it is going to be for the passengers or pilots who engaged in diving activities.

A good practice is to have a “down day” prior to flight after any diving. But as we noted above, we must consider the MSL altitude at which flight will occur, not the 8000’ cabin pressure altitude that is commonly referenced. Many light aircraft will fly higher than this and certainly most cabin class business aircraft will fly higher than this altitude. Two days might be a better plan. This is especially true in aircraft in which flight take place at higher altitudes that are not pressurized.

Using Dive Computers for Safety

Like aviation, technology has become commonly used in the diving community. Many pilots use iPads to help them with charting and calculations as they fly. Many divers now use computer or tablet based dive planning software and computers that go with them when they dive.

Like aviation, technology has become commonly used in the diving community. Many pilots use iPads to help them with charting and calculations as they fly. Many divers now use computer or tablet based dive planning software and computers that go with them when they dive.

There are ways to do the math, but if you are anything like me, I hated calculus in high-school and college. I cheat and use dive computers that do the math for me.

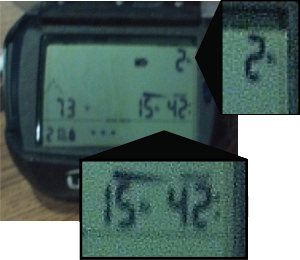

These dive computers continuously calculate a diver’s depth and in many cases, oxygen usage, and provide detailed algorithmic based computations that evaluate a diver’s activity and provide detailed data that a pilot can use to help evaluate when a diver will be safe to take as a passenger on an aircraft. Dive computers are a critical part for many divers safely conducting dives to and beyond recreational diving depths. A key feature that most dive computers include that is of use to pilots, is a “time-to-fly” calculation.

The “time-to-fly” calculation that is included in most dive computers is computed as the diver conducts their dive(s). Dive computers will calculate how much time after the last dive a diver makes is required prior to an individual being “back to zero” [considering how much nitrogen is likely to be in the diver’s body] and able to fly. If the same computer is used throughout a sequence of dives, it will calculate based on cumulative dive considerations.

The “time-to-fly” calculation that is included in most dive computers is computed as the diver conducts their dive(s). Dive computers will calculate how much time after the last dive a diver makes is required prior to an individual being “back to zero” [considering how much nitrogen is likely to be in the diver’s body] and able to fly. If the same computer is used throughout a sequence of dives, it will calculate based on cumulative dive considerations.

Most dive computers are very simple to use and a pilot will easily be able to determine if a “time-to-fly” calculation is being displayed. This simple task can be a critical part of helping determine when a passenger will be fit for flight after a diving trip. It would be a very good practice to make sure your passengers (and obviously you as a pilot) used one of these computers when diving and then intending to be on a flight. A savvy pilot would not accept a passenger whose “time-to-fly” calculation had not returned to “zero”.

Some tips that can be helpful:

- Ask any divers before they dive if they are going to be using a computer. If they have a choice, they should use the computer.

- Divers should use the same computer for the entire sequence of dives they will be doing. If a diver switches computers during the trip the computer won’t calculate the cumulative effects of their dives properly.

- Divers should be able to show their pilot their computer after their last dives are completed and prior to flight. This will help advise a pilot of how long they need to be on the ground prior to the expiration of the diver’s “time-to-fly” calculation.

Engaging Pilot’s and Passengers in a Discussion about Diving

Pilots and the passengers who are going to be diving on a trip don’t necessarily always communicate very well about these factors. Whether you are the pilot or the passenger, don’t hesitate to discuss with each other the question of how any diving plans may affect the next scheduled flight operation. Doing this is the best way to allow appropriate planning to be done for any needed down time between dives and flying.

For a pilot who is travelling personally with friends and may be diving with them on a trip, the discussion may be natural and much easier. When a pilot is hired to fly a customer to a destination, there may be much less interaction with the passengers about their itinerary or the activities they have planned on the trip. It is even possible that the crew that picks up the passengers is not the same one that dropped them off at their destination.

If you are the pilot, take the time to engage your passengers, professionally, if you believe there is any potential that they will be engaging in diving activities at their destination, even if you aren’t going to be the same crew that will pick them up. This will offer them the ability to plan ahead for equipment and scheduling needs if they are going to do any diving.

While it may seem awkward to ask passengers what they plan to do on their trip, it doesn’t have to be a full inquiry of the entire itinerary of their trip. If you know you are bringing passengers to a location that is a regular dive destination, or if in a more obvious case, you happen to be loading dive gear onto the plan as a part of your passengers bags, a simple reminder that if they are going to be diving sometime between their last dive and the scheduled departure time will be required. Just mentioning this can be enough of an opener in a conversation to discuss just how much time will be required if they then indicate they do plan to dive.

If you are the passenger who has hired a pilot, don’t assume your pilot will know what it will take for you to be safe to fly home. If you are planning on diving, talk with your pilot even before you dive to discuss when you will be flying again and under what type of flight conditions so you can plan your dives accordingly.

Doing this ahead of time can reduce the risk that a passenger will show up at the aircraft expecting to fly to the next destination (or home) only to find out at the last minute that the period of time between a last dive and their planned flight is insufficient to be safe.

I would note that not every dive destination is as obvious as others. A trip to Key West or Cancun may be an obvious location that diving is expected, but some places are less commonly noted as diving destinations. The Great Lakes offer some great diving (albeit cold), a trip to Puerto Rico for business could easily be paired up with an extra couple weekend days of diving, or even a trip to Atlanta could include the lesser known dive in the Atlanta aquarium. Any of these dives could be something that a passenger could require additional time between their dive and their return flight. If you are a passenger who is planning to dive in a location that may not be obvious to your pilot, make sure you bring it to their attention.

While most pilots have heard a little bit about not going flying right after scuba diving, most have not dove more deeply into some of the concerns and how they can deal with the potential considerations, especially if they are going to be professionally flying passengers who may have engaged in diving activities. This is an area of knowledge that most pilots can stand to have a deeper understanding, and with that understanding, can more safely provide recommendations to their passengers.

Divers have typically been advised to wait a period of time before flying assuming that they will be flying on a commercial airline that will typically pressurize their cabin at 8000’ mean sea level (MSL). While the recommended procedures by dive training agencies may be appropriate for these flight environments, they may not be sufficient to avoid all potential dangers if a passenger is going to dive then fly in non-pressurized aircraft or at higher cabin pressure altitudes. We can’t expect a diver to know everything about flying, but if they know enough to ask their pilot more about the flight environment, they may be able to more accurately mitigate any potential risks that could be encountered after diving.

Want to learn even more? The Divers Alert Network (DAN) offers another article, Flying After Diving — Cracking the DCS Code by Anthony K. Almon.

Divers and pilots shouldn’t skimp on safety considerations when considering flying after diving activities. More time is always better and you should never assume pressurization systems will work properly through all flight operations. Proper planning is important; it may be a matter of life and death. Now that you know a little more, help spread the word to other pilots and divers. Diving and flying incidents are rare, but with better knowledge, they should all be entirely avoidable.

The gist is that any mixing of diving and flying does result in some level of risk. The shallower and the shorter the dive or dives and the longer period of time between dives and flying, the lower the risk. The more frequent, the deeper, and the longer the dive or divers and the shorter period of time waited before flying, the greater the risk.

If you ever find yourself concerned that a diver is experiencing decompression related symptoms when going flying, there is an important resource to have in at your disposal.

Call the Divers Alert Network (DAN) Emergency Hotline at 1-919-684-9111 to talk to an expert in diving medicine. You may call collect. DAN medical staff is on call 24 hours a day to handle diving emergencies. They will be able to direct you to the best resources to handle the situation.