Lately I have been asking fellow pilots and applicants on practical tests an interesting question. One that hopefully they never need to know the answer to, but one that if they do need, can make a situation much better.

The question is prompted by a conversation with a friend who is an Aviation Safety Inspector for the FAA who not too long ago got to work with pilots who had “busted a TFR” during the election season at a specific travel event for one of the candidates. In that conversation, he noted that of the six unlucky individuals who strayed into the TFR at that time who ended up getting intercepted, not a single one of them tuned to the universal emergency frequency to attempt contact with anyone who might be attempting to communicate with them, namely the military aircraft that was approaching them.

That kind of surprised me.

I know, intercept procedures can seem a little daunting and most of us don’t commit them to memory because we hope we will never need them.

Some of us keep them on our kneeboards as pilots, but that number isn’t as many as it probably should be either.

So I started asking fellow pilots and practical test applicants a question.

“Imagine you are flying along, and an F16 pulls up alongside your wing. What is the first thing you would do?”

The majority of pilots fumble the answer. A few practical test applicants and pilots start talking about digging through the FAR/AIM or documents in Foreflight on their iPad to figure out what to do.

Can you imagine the F16 pilot watching this from their cockpit as you fly along digging through the FAR/AIM trying to figure out what to do? How long might that take? It might be kind of humorous for them actually.

Only a very few I have asked have answered, the first thing they would do is turn to 121.5 and follow directions being given to them.

I blame us as instructors, DPEs, and fellow pilots for not drilling this into each other.

A TFR bust isn’t always the fault of the pilot. It can happen to anyone. Sure, TFRs that are published and can be learned about prior to flight shouldn’t be something pilots encounter if they are properly briefed and planning is done correctly. But in some cases, TFRs do pop up after you have already started a flight. A downed aircraft, an emergency situation on the ground, or a security situation developing can make these pop up even while you are in the air and it is possible to encounter one even with proper planning having been done.

In a case like this, an intercept handled properly could end up being a no-harm, no-foul situation for a pilot who responds properly to an intercepting aircraft and/or directions from ATC.

So, remember if nothing else from this quick tip.

Tuning to 121.5 for intercept is a good starting point if you happen to get intercepted.

Want to know more?

Digging into some more details can’t hurt either.

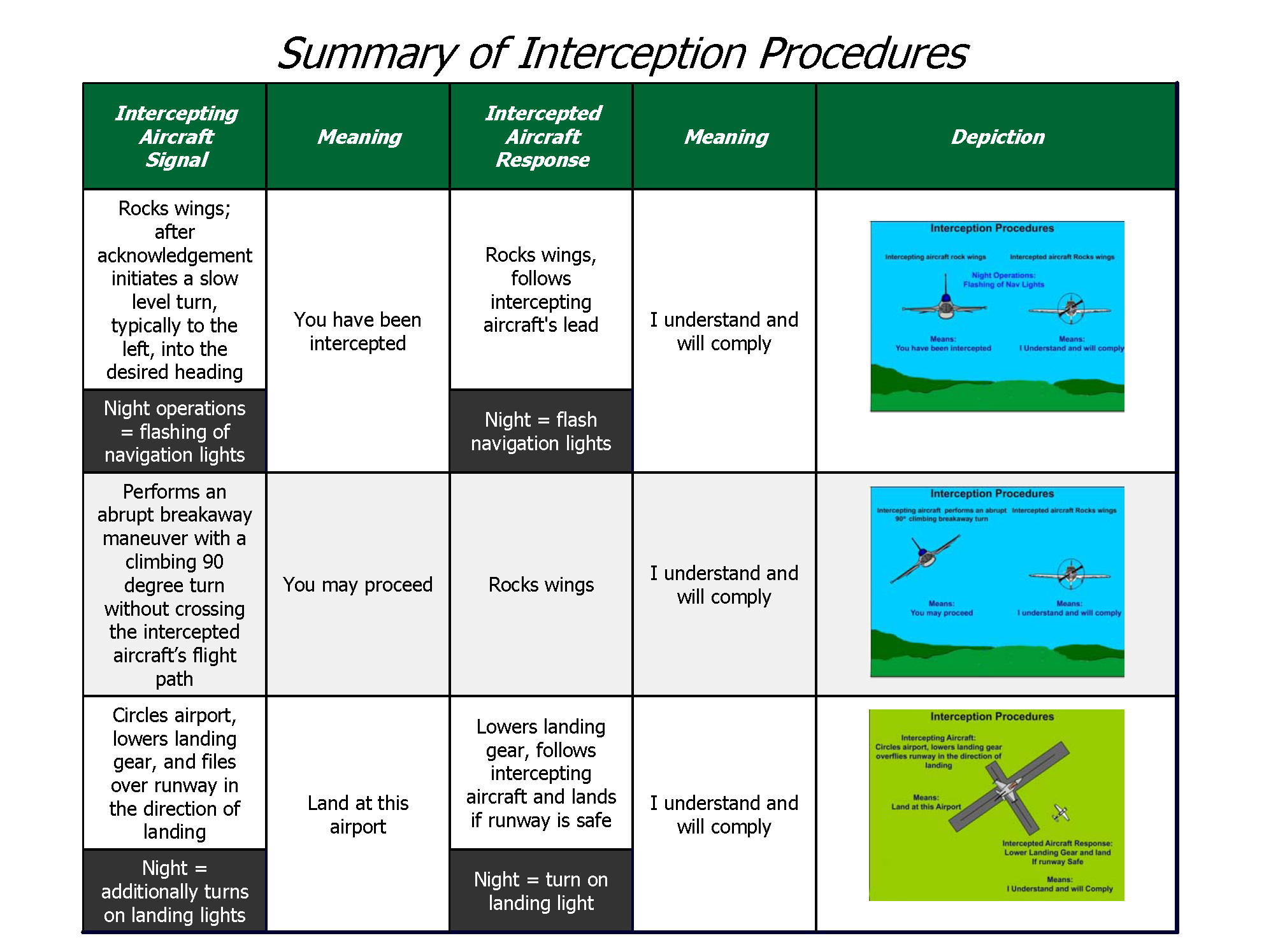

The graphic below comes from an FAA publication that offers a broader Summary of Intercept procedures. You can find this at:

https://www.faasafety.gov/files/gslac/courses/content/24/293/Interception%20Procedures.pdf

Another version can be found at:

Another version can be found at:

https://www.faa.gov/news/safety_briefing/2015/media/intercept-procedures.pdf

Want to read some more from the AOPA libraries?

Check out the AOPA Planning and Intercept Checklist at:

Or the NORAD / FAA Intercept Prodecures PDF at:

https://www.aopa.org/-/media/Files/AOPA/Home/Flight-Planning/NORADandFAAInterceptProcedures.pdf

Any of these might be great additions to consider for your digital flight bag or printed for your kneeboard.

In any case, remember that talking with ATC can help avoid an inadvertent TFR bust, but if you aren’t doing that, and happen to get intercepted, start with 121.5 to communicate.