The Kissimmee Gateway Airport (KISM) in Florida recently announced it was implementing landing fees for all aircraft with some limited exceptions.

Implementation of per-landing fees at federally funded airports such as Kissimmee airport has long been discussed but also fought in the aviation community. There are many reasons for this, some of them safety-related.

The fee structure is $3.00 per landing, touch & go’s included, per thousand pounds of aircraft weight (at maximum gross weight or maximum landing weight, whichever is lower). For an average 2,550-lb Cessna 172, each landing would cost $9.00.

The current policy does offer some exemptions, although these will not reduce the burden on aircraft in the area who want to use the Kissimmee airport for proficiency, training, or safety decisions.

Those aircraft exempted from the landing fees include based aircraft, government, federal and military aircraft, aircraft that are air ambulance or firefighting, and those that are involved with angel flight activities. An additional exception was noted for the “first landing fee per calendar day for aircraft under 5,000 lbs.” So, a transient light general aviation aircraft coming in or out would not likely incur the cost if they only landed once a day.

But those aren’t the only kinds of aircraft that land at this airport. Specifically, if we consider how this will affect aircraft engaged in flight training, it will result in either a per-landing cost or serve to drive them away from this airport.

Perhaps this is precisely what the Kissimmee City Commissioners want.

But there is a reason we have a National Airspace SYSTEM. I bold that because the safety in our system is because it is an entire system, not just the work of one airport that keeps us safe.

The Kissimmee airport receives Federal Aviation Administration (Department of Transportation) funds to help make it a good part of that system and one that does not dissuade the use of the airport by non-local aircraft.

Concern is brewing in the flight training community that airports such as this one will begin to implement this practice at more airports, driving negative impacts on costs and safety in our national airspace and pilot training system.

What do I mean by this? Well, let’s discuss a few potential consequences of implementing landing fees like those in this policy.

Pilots seeking to remain current will avoid the airport or do less landings.

One would hope we never come to this point, but if a pilot is seeking to work on currency efforts in their own aircraft, we can see how an operator might choose to fly only the minimum number of landings to remain current; avoiding more landings to establish true proficiency if there is a cost associated with every landing.

A pilot flying practice approaches to the KISM airport might want to land and get a practice landing in also, but with the landing fee, while I understand it might be nominal, might choose to just go missed and skip that landing for additional proficiency. Remember, landings count, but approaches don’t, according to their policies.

Additionally, the landing fee isn’t the only barrier; the hassle of dealing with it is also present.

There is another airport, KBFA, that I used to fly into a few times a year, which instituted the Vector Systems landing fee process. Since they have done it, I have honestly cut my trips to that airport by at least half, not just for the landing fee cost but also for the hassle of dealing with it. All these little things make pilots make decisions that might not be as foreseeable at the outset.

Traffic avoiding the airport with fees will be driven to other airports, driving higher traffic density and decreasing safety margins.

It isn’t hard to imagine that a reduced airspace capacity to handle aircraft due to pilots avoiding an airport such as Kissimmee will drive that traffic to neighboring airports. If too many airports do this, the airports left without fees associated with training efforts will become heavily taxed with traffic and reduce traffic separation. It is easy to understand that too many aircraft at one airport puts them in a position where it is more likely they play bumper planes. And last I checked, bumper planes is bad. Our training system is safest when we have multiple options for airports and aircraft can spread out.

If we start implementing landing fees at a hodge-podge of airports throughout our system, pilots, especially those in training, are going to seek out use of airports that do not have such fees. Especially when they need to conduct multiple landings in a particular flight for training or proficiency reasons. This will drive more traffic to airports that are less able to handle busy operations, reducing safety.

Increasing training costs with landing fees.

If I look at my own personal training back a few years ago now, I see that by the time I had done my private pilot certificate, instrument rating, and commercial pilot certification, I had about 680 landings. If I used that $9.00 per landing number, I would have had a cost footprint of about $6,120.00 just for landings! If we take a commonly quoted number of around $65,000 for training costs to this point in our modern aviation training system, this would represent a little over 9% of the cost of training just for the cost of landings. Remember, pilots in training make multiple landings per hour in their training efforts.

Isn’t it going to be a great revenue source for the airport?

Well, I am sure that the airport administration has been led to believe that this will generate revenue for the airport above and beyond what they currently receive. But the reality is that it is actually more likely to drive revenue away from the airport. Landing fees make pilots make decisions to go somewhere else. And that means that the businesses at the airport that sell fuel and other services lose that business. It also means that traffic count will go down, which is something that airport funding, and the basis for having a control tower, is based on in many cases. It is very possible that landing fees on light general aviation and training aircraft will do more damage than good to the airport. But that is something that you have to dig deeper into to understand.

Billing isn’t necessarily going to the pilot who did the landing.

The billing agent, the company collecting the landing data at Kissimmee (and many other airports implementing this system), is Vector Airport Systems. This company collects data about landing aircraft through the use of camera systems and bills the registered aircraft owner according to its billing authorization letter. Aircraft that are rented or in which flight training is conducted are frequently not owned or flown by the registered owner of the aircraft. This means that the aircraft provider now is going to get bills and have to go back and track down who was flying the aircraft at each landing, potentially multiple different people per day, per week, per month, and bill that back.

But let’s be honest: The airport doesn’t care about this part. It isn’t their problem how the bill gets paid; they have a third party they have contracted to do this for them. If I were a provider of an aircraft for rental or instruction, I would charge for that tracking effort also. Or I would just ban my aircraft from going to airports with these systems in place.

Implementing landing fees like this at the outset may sound simple, but it drives many more complexities and potentially downstream consequences. Some may even reduce safety.

Our national airspace system has worked well for many years without per-landing fees. It works best this way, and changes to that are going to have consequences for those who want to use the system and those who think that these fees will somehow improve their revenue positions for their facilities. I personally don’t think they are going to deliver as predicted.

I encourage those engaged in the flight training community to learn more about this policy, and engage on their local levels to make sure their local airports don’t implement policies like this also.

You can find the entire Kissimmee policy by clicking here.

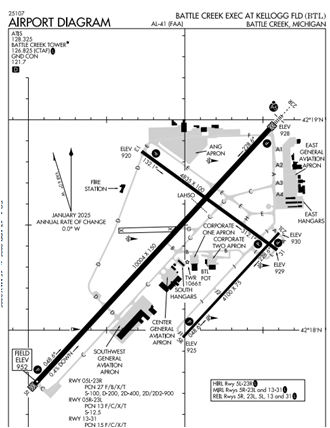

A parallel runway at a heavily used training airport significantly enhances safety by segregating traffic, reducing congestion, and minimizing collision risks. Training airports host numerous student pilots practicing takeoffs, landings, and touch-and-go maneuvers, which increase runway occupancy time and airspace complexity. A parallel runway allows simultaneous operations, separating training flights from other traffic, such as commercial or general aviation, thereby reducing the likelihood of conflicts.

A parallel runway at a heavily used training airport significantly enhances safety by segregating traffic, reducing congestion, and minimizing collision risks. Training airports host numerous student pilots practicing takeoffs, landings, and touch-and-go maneuvers, which increase runway occupancy time and airspace complexity. A parallel runway allows simultaneous operations, separating training flights from other traffic, such as commercial or general aviation, thereby reducing the likelihood of conflicts.