When you ask most people where they think most pilots train to become airline pilots, they will answer “at a college or university.”

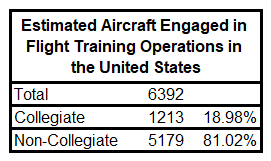

The data I have accumulated so far indicates that less than 20% of the aircraft we referenced were used in flight training in the collegiate environment. That means more than 80% of our flight training in the United States using this data is likely provided at local FBOs and flight schools, academy-style training operations, or large flight clubs.

The bulk of our training fleet that is used to provide training for pilots, professional ones included, is not likely in the collegiate environment.

What I ended up finding was a total of 6392 aircraft so far with only 1213 of those aircraft being in collegiate training programs. This leaves the bulk, over 80% of the fleet, in non-collegiate training operations.

(These numbers are as this was written – if the numbers in the spreadsheet below are now different it is because I am getting more information add adding/updating it as it comes in)

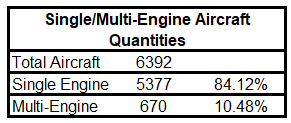

To no real surprise, it can also be seen that the bulk of the fleet is single-engine aircraft. With a much smaller percentage of the fleet being multi-engine aircraft (approximately 10%).

To no real surprise, it can also be seen that the bulk of the fleet is single-engine aircraft. With a much smaller percentage of the fleet being multi-engine aircraft (approximately 10%).

Our training fleet is likely smaller and less sourced from collegiate aviation programs than most would think based on this data.

How the data was sourced:

I got curious about this over the summer and decided to pay someone to go dig data up on flight training operations of all types in the United States and what they had in their aircraft fleets. I wanted to know what planes were out there actively engaged in the provision of flight training.

I suspected that we would find that there were more aircraft being used outside of the collegiate environment than were used in their programs, but what we found showed that is the case even more than I suspected.

The list provided here was dug up by referencing collegiate aviation directories, and aviation flight training directories, scouring webpages for lists of flight training providers, referencing the providers’ webpages, and literally calling and emailing places and asking them how many planes and simulators they have.

I personally paid a guy to do this. I wanted more information.

Admittedly, this data is a point-in-time capture. It doesn’t track ups and downs in fleets. That being said, there is nothing in the FAA registry process for aircraft that denotes that an aircraft is “used for flight training” and I am aware of no other place where such a data point exists. If someone out there has a better source of data than this, please share it with us in the industry.

The good news is that most flight training operations, especially the collegiate ones, are pretty willing to promote their fleets, what they offer, and how big they are. This helped the data collection process.

Is it a complete picture of the available training fleet?

No.

I know there are probably a few hundred smaller flight training providers, individuals providing training in clubs or in a single aircraft, and even probably a couple of mid-sized fleets that are missed in this data. If you are reading this, and know of any that are missing, help me fill in the data.

The missing data might mean even fewer people are trained in collegiate aviation.

Ok, so there are some assumptions in my data, but they might actually make the numbers even more pronounced. It is far more likely that I am missing smaller FBO-based training operations, mid- to small-sized flight clubs that offer training, and single aircraft training providers in this data set. If we added more aircraft to my list, I honestly think we would be more likely to add more non-collegiate aircraft into the mix than find that I missed large training fleets in the collegiate environment.

What does this mean for the training industry?

Well, that’s a good question. At a minimum, it might mean that our sense of where the bulk of hours of flight training, where the most ratings and/or certificates are completed, and who offers training to the main portion of the pilot training pipeline may have developed based on faulty assumptions.

It also means that we might not have as much “flex capacity” to increase the training numbers as we might hope.

Are there enough aircraft?

I don’t think so.

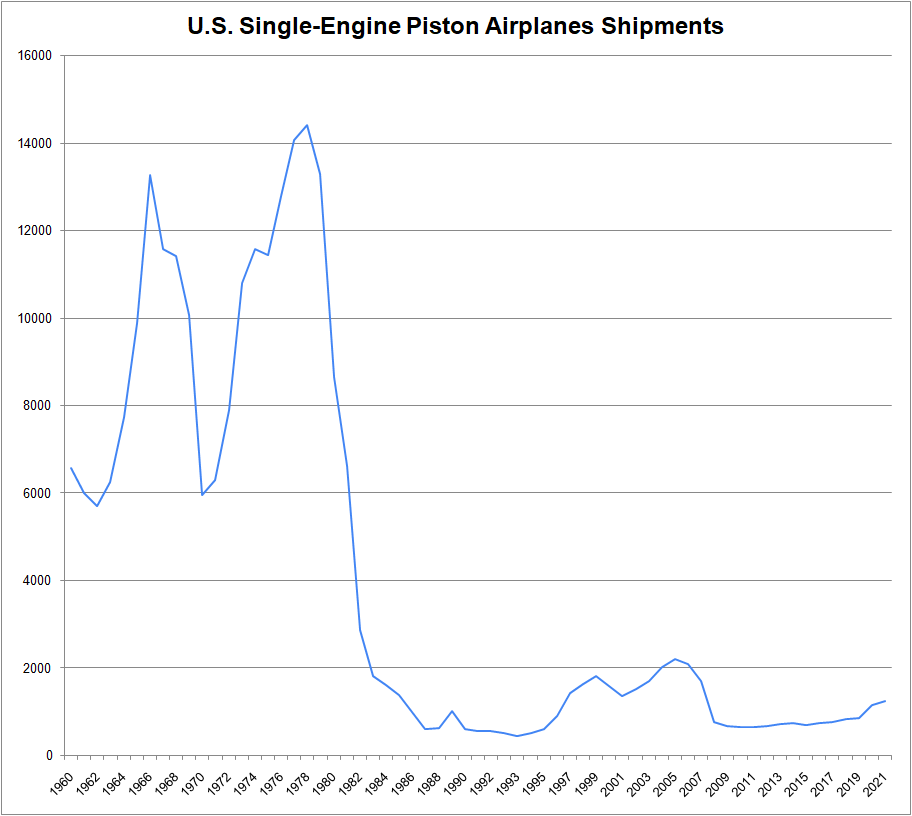

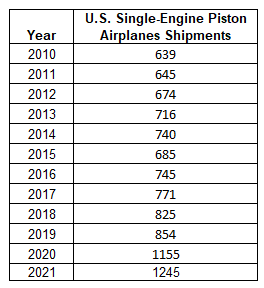

We know that airplane shipments in the single-engine piston category are significantly down from historic levels experienced in the 1960s and 70s. In the past few years, we have seen few years top the 1000 aircraft delivered mark.

Many flight training operations are relying on older aircraft from the 1980’s, 70’s, and even 60’s that they keep running with good maintenance to keep their training provision going. No matter how much good maintenance you do, they can’t last forever, especially in a flight training environment.

Many flight training operations are relying on older aircraft from the 1980’s, 70’s, and even 60’s that they keep running with good maintenance to keep their training provision going. No matter how much good maintenance you do, they can’t last forever, especially in a flight training environment.

As these aircraft wear out, we are not making enough to replace them. Adding to this, current supply chain delays are putting new orders of aircraft for many training operations out 2-3 years or more. Prices are increasing on these orders at the same time. Overall, the number of training aircraft available in our system is declining.

The result of this has been conversations with many I know in the industry that believe we are “maxed out” when it comes to the number of pilots we can produce in our current system. If there aren’t more aircraft, changes in how we train, or different certification processes, we may have reached our maximum output potential when it comes to pilot training in the United States.

I don’t say this to indicate that there is no solution. In fact, I think there are lots of solutions. I even have a few ideas that might help. But I think we all need to consider this infrastructure piece as a part of the pilot training pipeline landscape as we work to source our future workforce.

Input on this is welcome, and certainly, if you see missing data, please share it with me. I am making my spreadsheet publicly available on this post. If your flight training operation is missing, get me the data. If you know of one that is, help me get the data. The better data we have, the better we will be able to understand our industry and make changes to improve efficiency and the amount of training we all provide.

Great job putting this together Jason. I’ve watched the non-collegiate training grow faster than most collegiate training programs. Educational institutions (in my opinion) respond slower to various demands. There is always a variety of hoops to jump through to make changes as compared to the non-collegiate environment. Private enterprise has the ability to respond quicker to demand. At the collegiate level you are competing with many other programs that perhaps want a bigger budget too. I think technology, training aids etc. has helped the private sector a lot. Based on my history with collegiate flight programs – I strongly support those programs. The learning environment is based on a broader spectrum. I’ve never seen the demand as good as it is now – it’s exciting to watch the advancement of so many collegiate graduates. I believe both sides of the training environment play a major role in helping this demand. Occasional I see articles talking about the exploration of single pilot cockpits. I just hope that exploration isn’t driven by demand instead of things like safety etc.