‘Tiz the season for cold weather flying, and in a few cases, pilots may find the opportunity presents itself to do a few landings on a frozen lake or two!

For pilots from the further north, the question of whether to do this is not a matter of if, it’s just a when each season these landings become a part of normal general aviation operations. Sometimes, the ice is in better condition than the runways! Southern pilots who have never done this may think we are crazy, and those of us that live in the middle zone of the country (I happen to live in Michigan), find that we get lucky enough with the right conditions to be able to do this some years and not others. With that said, under the right conditions, there is no reason it can’t be done safely.

Now, there are a bunch of precautions that I obviously must recommend, but when the conditions are right, it can be a unique and pretty fun way to spend an afternoon of general aviation flying.

First question, is the ice thick enough?

First question, is the ice thick enough?

Naturally, no-one wants to sink their aircraft to the bottom of a frozen lake. So, making sure the ice is thick enough, and I mean consistently, is the first task to even start thinking about if you are going to try to make some landings.

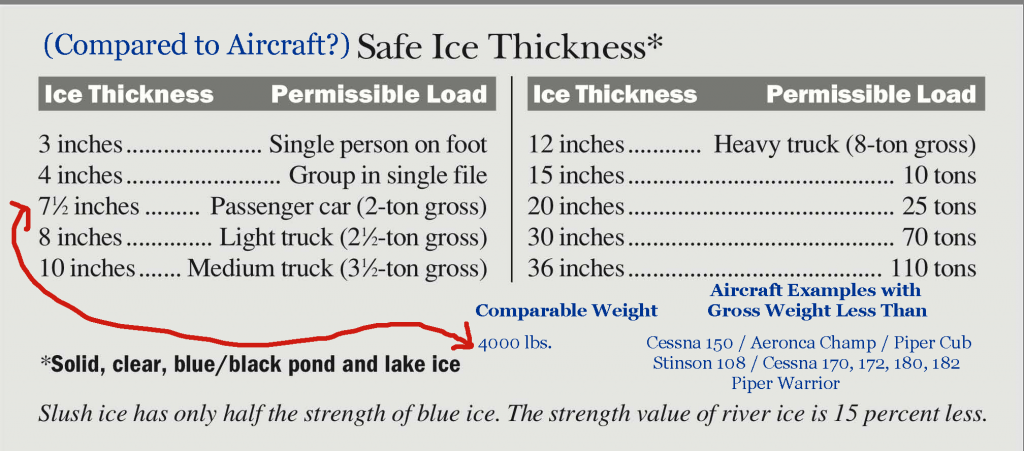

There are general rules of ice thickness that can be considered for comparable objects, such as people, vehicles, or other things. If we extrapolate those weights and compare them to some aircraft, we find that for most general aviation aircraft it is a good idea to make sure there is at least 7- 8 inches of ice before considering any landings.

This means a consistent depth of ice like this, not just a little near the shore that has gotten than thick. Before I do any landings, I get either reliable reports or personally go drill some holes near where I plan to land to ensure that the ice thickness meets the expected needs.

Can I land there?

In most places, the rules about landing on a frozen lake are the same as they are about landing on a non-frozen lake in a seaplane.

If the lake is publically accessible, able to be operated on by other motor vehicles, and there are no restrictions given, it is likely that you may be able to land an aircraft there!

This doesn’t mean you have the right-of-way to operation though. You do still need to make sure the ability to safely land without encumbering or endangering other users of the ice is guaranteed. Just because you are on final approach to land, doesn’t mean that the 4-wheeler that is cutting in front of you has to get out of your way. In fact, it is highly encouraged that you be ready to go-around at pretty much any point. Landing on the ice isn’t something that is all that frequent, and most other users of the lake will probably be surprised to see an aircraft in the process of landing. They are unlikely to be in the habit of “checking for traffic” above them as they head out to ice fish or maybe go ice boating.

Do I need skis?

Yes, and No. It depends. The main thing it depends on is the depth of snow, what tires you have on your aircraft, and to some degree, how long the lake is. You are going to be typically operating using soft field takeoff and landing procedures, and with a little snow on the ice, it is going to take more “runway” to get off the ground. If you have a longer lake, a couple inches of snow may still allow you to takeoff in a sufficient distance. If the lake is short, or the snow is getting deeper, you may find that the performance limitations mean you won’t ever be able to safely take back off.

Skis definitely help as the snow gets deeper, but even then, there is a limit. Hard packed snow is going to support the aircraft better than a fresh dumping of 12 inches of light and fluffy stuff. Conditions make a big difference here. It also can make a difference if you have main wheel skis, or also have a tail ski.

Bigger wheels can help also. While a cub with 5.00 tires may not be great in the snow, one with some bushwheels may do just fine. I used to regularly operate a 7AC champ with a 115hp engine and 8.00 tires that did great in up to about 3-4 inches of snow. You are going to have to know your aircraft, know the conditions, and practice a little to do this safely.

While you may choose between skis or just do it on the wheels, I do generally recommend removal of wheel pants, however. Wheel pants can easily get filled with snow, help pack ice into breaks, or even just do damage to the wheel pants themselves when operating on ice. Heck, the reality is that I take them off most aircraft I operate (assuming it is FAA approved) during most winter operations on any runway for the same reasons.

Tailwheel? or Tricycle?

I have landed both on ice. Some pilots will tell you that you should only do it using a tailwheel aircraft because if you catch a nose wheel in a hole or crack it will be more likely to collapse and cause problems than when you catch a tailwheel. Certainly, catching a nose wheel may cause a collapse that causes the prop to strike and engine damage, but a tailwheel catching can cause problems also. In many cases, the tailwheels are smaller and even more likely to fall prey to a hole in the ice. Shucking a tailwheel off leaves the pilot skidding the tail just as much as collapsing a nose gear leaves a pilot plowing the cowling. Either is bad. But it doesn’t mean that one can or cannot land on ice. Remember that soft field technique you learned when you got certified? Here is a place you should definitely be using it, no matter if you are in a tailwheel or tricycle gear aircraft.

I do tend to stay away from using retractable gear aircraft on the ice, but that’s just a personal preference. I can’t say I have much logic that is founded on anything as a reason. Many pilots have very successfully operated retractable gear aircraft safely from properly considered ice landing areas.

Generally, when is it right?

It’s a bit of an oversimplification, but later in the winter is typically better. More ice has developed and snow loads may have compacted or melted away. The general best conditions are thick ice with minimal snow. Anything other than that, it starts getting more questionable.

Some of the dangers.

- It’s slippery! – I know, this seems simplistic, but you are landing on ice. Plan on sliding some. Keep braking to a minimum and watch your directional control;

- Rough “runway” conditions – Except in few rare instances, the runway isn’t going to be smooth and plowed. This can be rough on the landing gear in extreme conditions.

- Too deep of snow – Either across the entire surface or sometimes in drifts, deeper snow can be a catch for the aircraft. Hitting too deep of snow can ruin a takeoff, make a very short landing roll, or in extreme cases, flip an aircraft.

- Ice fishing holes – Holes in the ice from where people have fished can quickly become a pothole your gear falls into. Where spearfishing is frequent, these holes can be very large. Sometimes these holes are hard to see because they have frozen over the night before after use and been covered by snow again. I try to land away from where people regularly fish. But keep in mind, if people aren’t fishing there, it may also be because the ice is too thin for them to go there.

- People / other users of the ice – I mentioned it above, but you are going to have to make sure your landing and takeoff areas are clear of other users. Enough said.

- Obviously, thin ice – Ice doesn’t stay consistent all the way across a body of water necessarily. Some local knowledge can help, talk with fisherman who have drilled holes if you can, or check more than just one place if it is in question at all. Ice on rivers, on backed up lakes behind dams, or any body of water with springs can sometimes never freeze properly.

- Oh, and your insurance may or may not cover it if there is a problem – Just worth mentioning. If you land on them, and something goes wrong, it is possible that your insurance won’t cover any problems. Take the risk at your own risk, but know before you go.

A more structured option.

Don’t want to try this on just any lake near your home airport? That can be a good idea if you aren’t proficient and comfortable. There is an option that is a highly structured approach to doing an ice landing that crops up every year (when the ice is right). The Alton Bay Seaplane Base/Ice Runway out in New Hampshire plows, takes care of, and updates information about their runway regularly. You can find out more information at https://www.facebook.com/AltonBaySeaplaneBaseandIceRunway/ if you are thinking about a trip to try out some of this ice landing stuff.

Do your homework first.

No matter what you do, if you are thinking about taking your aircraft onto a frozen body of water, do some research first. Make sure it is legal in the location. Check the ice, check the ice, and then check the ice again. Monitor weather conditions, ice conditions can change fast. Be aware of the dangers. And don’t be afraid to bail out on doing it at the last minute. Even if you are on final approach or touchdown and things just don’t feel right. Going home safely is always a better option than damaging the aircraft, your passengers, or, you.

Full disclosure here, if you go sink you airplane, don’t blame me. It really happens. Last year I got a call, you know, “since I am a scuba diver”, that my services may be in need for the picture below.

Check out an article from last year where the ice wasn’t thick enough:

Plane falls through the ice on Murray Lake

There really is some risk here, but it can be a lot of fun if you do it right. If all goes well, and the conditions get good this year, I am hoping to get a few planes together and do a cookout on the ice on some warm(ish) weekend afternoon. If the conditions aren’t right, it won’t be this year. Like it wasn’t last year, or the year before.