Scenic and uneventful. The best way I like to describe a ferry, transfer, or delivery flight, especially one of significant distance. If it is scenic, it typically means it is VFR and the travel can continue, and if it is uneventful, it means nothing major went wrong. It is what I always hope will be the outcome of a long flight.

When I got the call recently to help a new owner pick up an A36 Bonanza he was purchasing in Seattle, I looked forward to the trip but expected that the distance could easily result in some challenges for the flight.

With an intent to pick up the aircraft on the first weekend of April, I knew that the Rocky Mountains still held great potential for winter weather and that the significant distance for the flight left us with the potential of needing to plan for unexpected changes to any intended schedule and route.

This is pretty much the norm for any flights like this. It is always the hope that a flight of this distance will go off as planned, but personal experience has taught me that planning extra days, carrying extra days of clothing, and just hoping you won’t need it is always a good idea. In a sense, I typically take this almost superstitiously to ward off the demons of needing the extra supplies.

We set the date, booked the one-way commercial trip from Grand Rapids to Seattle for the two of us and waited for the departure date.

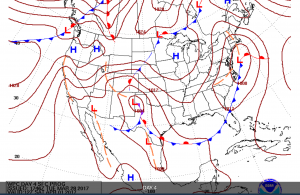

A couple days out from the proposed flight I looked at a prog chart and was encouraged to see high pressure systems predicted across the entire route for our departure date.

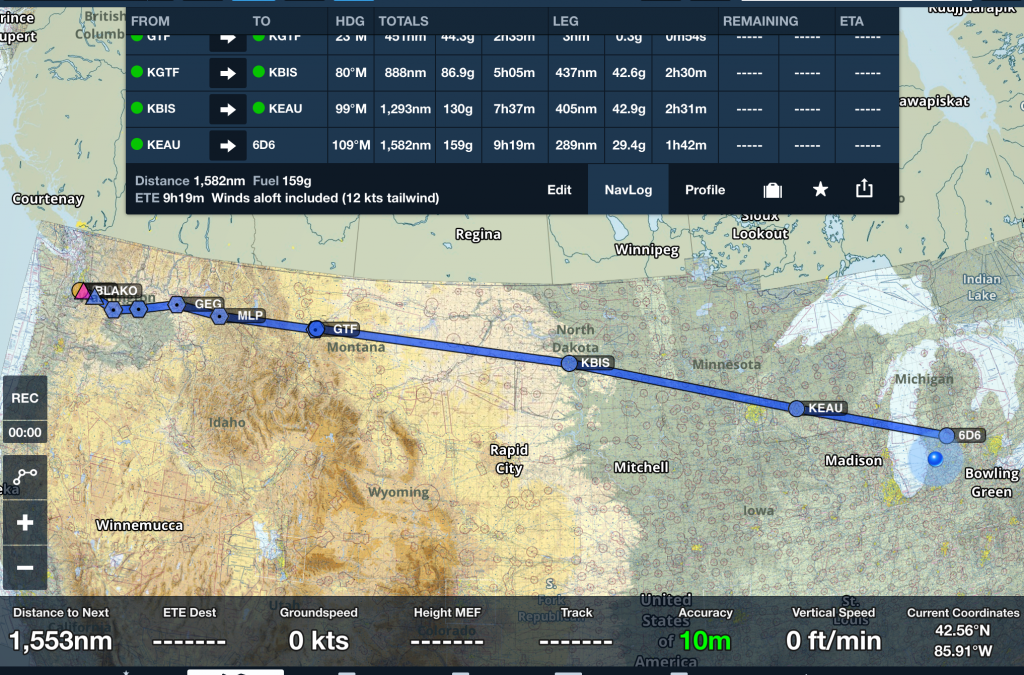

Hoping this would hold, I set a proposed route.

Any time a route like this is set, it is a plan, and a plan that may significantly change. It is a rare occasion that such a distance flight like this goes exactly as planned.

We left early on Saturday April 1, (yes, we planned an “April Fools” departure) flying from Grand Rapids on the 6:30 am Delta flight to Detroit, then to Seattle, arriving earlier than expected at 10:50 am local time. A quick cab ride got us over to the GA airport (Auburn – S50) where we were met by the previous owner’s maintenance provider.

The plane was ready, we pre-flighted thoroughly, and everything looked like it was in order.

The weather wasn’t perfect, definitely IFR with around 800 overcast being reported, but it was warm enough to go into the clouds IFR and the aircraft was capably IFR equipped, so we continued our planning.

The route wasn’t ideal, as there was high terrain across it and we were going to have to climb through cloud layers where the temperatures were going to end up below freezing and could result in icing conditions, but cloud tops were predicted to be low enough to be manageable and we expected we could climb to a cruising altitude where we would no longer be in IFR conditions.

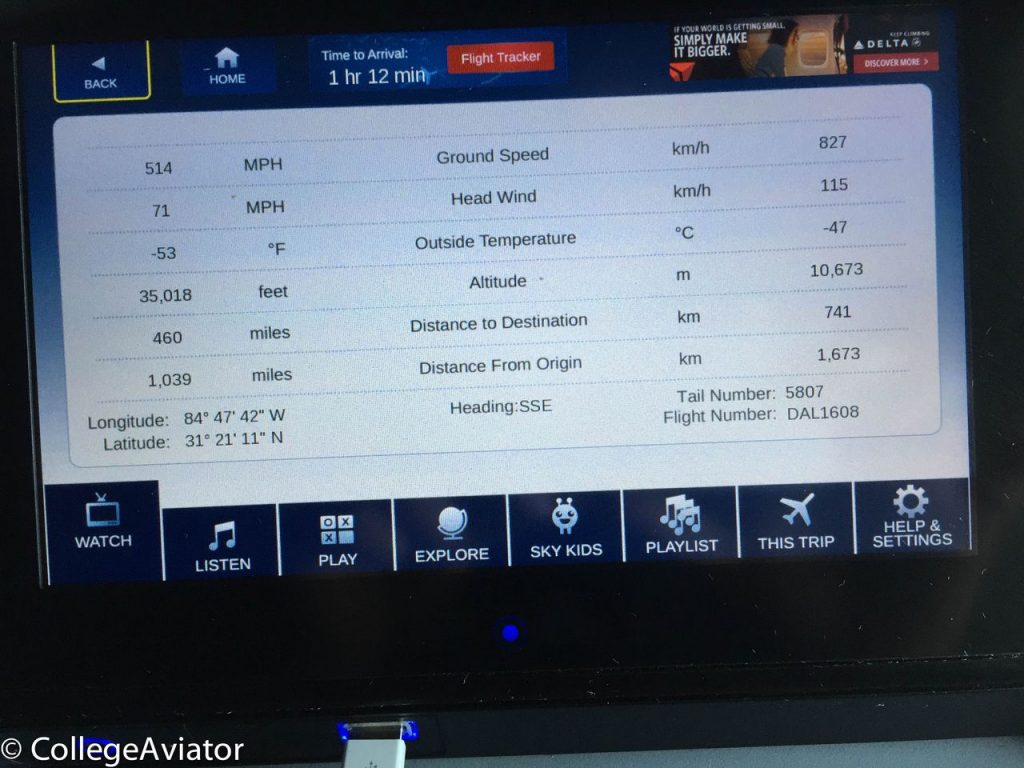

On a side note, I had found a new “non-FAA approved” resource gathering option to help determine where the cloud tops might be. Did you ever notice that the Delta In-Flight Entertainment (IFE) system can provide altitude and temperature of the aircraft along with other details?

As we descended, I watched out the window and noticed that we didn’t enter any clouds until approximately 10,000′ MSL and that there were layers of them with gaps as we descended into Seattle. I can’t say that the Delta IFE will always be a reliable pre-flight weather briefing information source, but with our departure time being shortly after our commercial aircraft arrival, it was a helpful source of data that confirmed some of the tops forecasting I had seen.

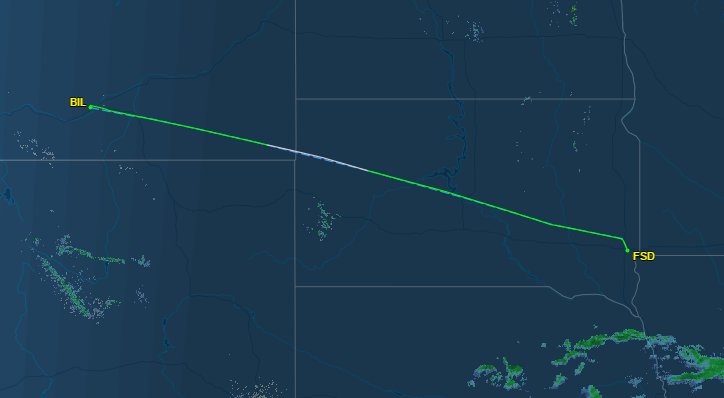

But this is where the route changed. To avoid some areas of moisture (clouds and rain), we used the satellite and radar imagery to make some route changes. A new destination of Billings was set as the initial stopping point instead of Great Falls. This also was a longer distance leg than we had originally expected because we were now able to take advantage of based on forecasted increased tail winds.

The A36 we flew is turbocharged and equipped with oxygen, so moderate altitudes was an option. It turned out it was a good thing.

Our departure put us into the clouds quickly, and as we climbed through the pass in the Cascades to the east of Seattle, we passed through and between layers of clouds to our filed cruising altitude of 13,000′ MSL.

We were fortunate initially to climb on top of cloud layers by around 7000′ MSL without any icing forming, and got the benefit of a beautiful view of Mt. Ranier sticking out of the clouds as we proceeded east.

With Mt. Ranier past, we started to see the clouds below us moving upward.

Not long into the journey, the clouds began to engulf us at 13,000′ and we ended up climbing to 15,000′ then 17,000′ to stay above them and out of any icing conditions. This was a little higher than we had wanted to climb, but with an oxygen system onboard we donned our cannulas and continued our cruise.

While we had to fly higher, the Montana high country did hold some beautiful scenery as we left the clouds behind along the route.

Just over 3 hours later, we arrived in Billings in VFR conditions.

It was still realatively early in the day when we arrived at 5:30 pm local time, so we fueled and set out for another leg.

Having made a longer than expected first leg we now needed to consider the fact that our next leg might cause us to arrive beyond closing times for many airport FBOs. We selected an airport with a 24 hour FBO for our next stop and we were off to Sioux Falls, SD.

The next leg was another long one, just over 3 hours, and by the time we arrived at around 10:15 pm local time, we were ready to call it a night. It had been a long day with the early departure from Grand Rapids, the cross-country commercial flight, and now over 6 hours of flying.

This is where the biggest challenge of our trip presented itself. Finding a hotel for the night.

Apparently Sioux Falls, SD was the happening place that particular evening with two rodeo’s, a concert, and a hockey tournament in town. Of the 54 hotels that were listed by multiple online booking sites, none had any open rooms. Fortunately, with a call to my girlfriend she managed to find us one lone room, and with a rental car from the FBO, we headed there to call it a night.

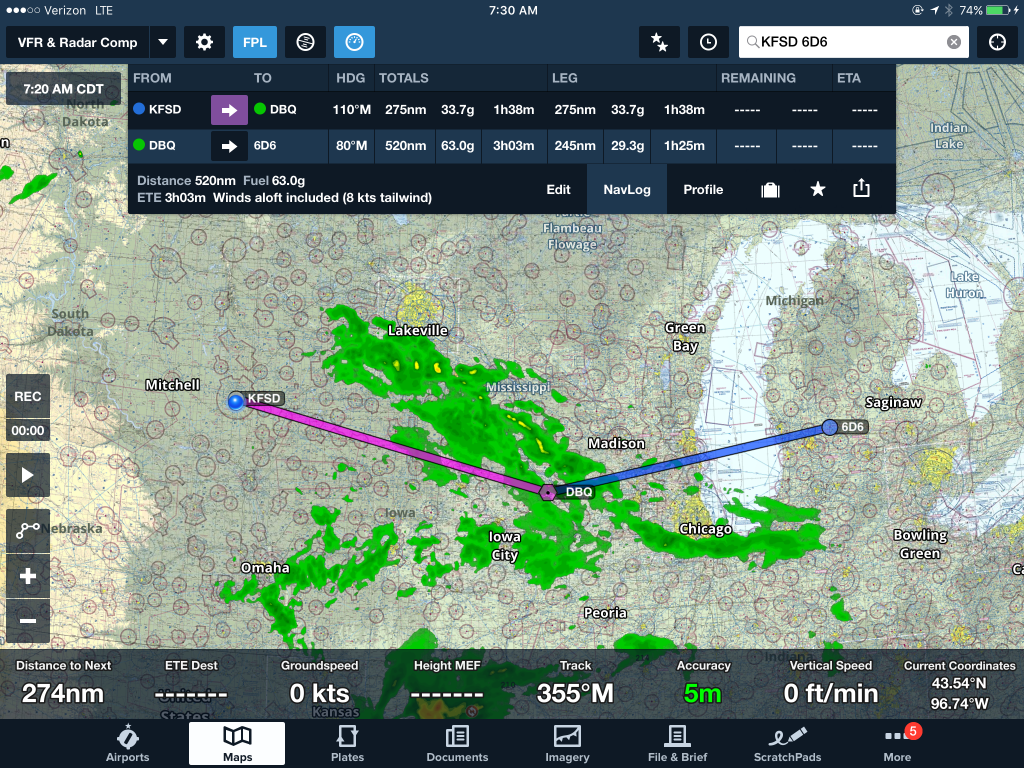

After some rest, we woke the next morning, checked the weather again, and found a mostly clear path to our destination, home.

Grabbing a quick breakfast, we drove back to the FBO, returned the car, pre-flighted, and were off for one last just over three-hour leg.

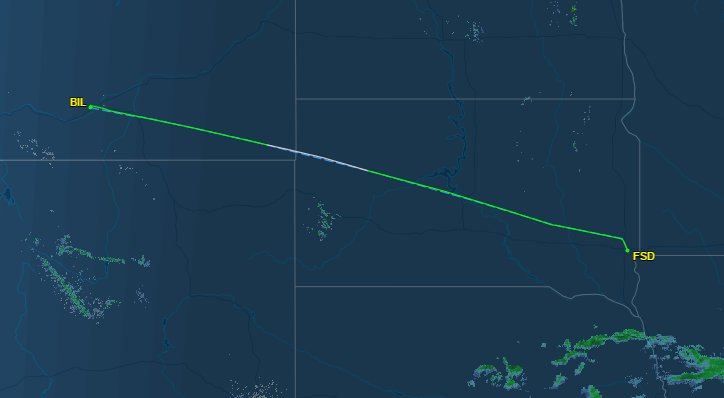

The leg wasn’t perfectly straight due to a little weather but was easily planned around.

In the end, and with the help of some onboard ADS-B weather data, the route ended up getting cut a little short as weather moved and dissipated anyway.

Amazingly, we were home just after noon on Sunday.

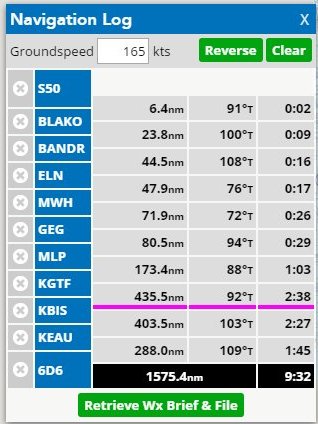

When you look at the originally planned route for this trip we see that it really wasn’t that much different than what we ended up flying.

Original Route Planned

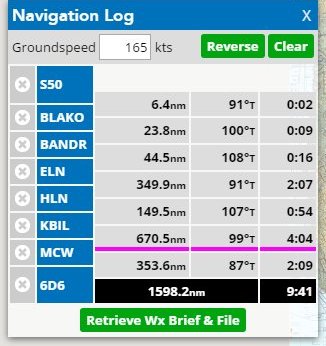

Route Actually Flown

The difference in distance was a mere 22.8 miles and 9 minutes planning, with the actual time flown being 9.6 hours across the route even though we didn’t stop at any of the places that were initially planned.

Across a distance flight such as this, major changes many times result in very small incremental changes in the entire footprint of the trip itself.

This is where flexibility comes into play and can offer the pilot much greater opportunity to get a flight done than if there are committed to a specific plan. Plus, sometimes it can result in an adventure!

Original Route Planned

Route Actually Flown

Flights like these are dynamic, challenging, and rewarding all at the same time. While many pilots fear long distance flights such as this one, they are entirely possible in GA aircraft for careful and considerate GA pilots. The psychology, resource planning, and flexibility on flights like these are all topics that could be considered in many in-depth discussions and articles, and are all factors in making flights like these successful. But in rare cases such as this one, everything comes together with minimal changes and the flights are completed almost exactly as planned.

Nice cross country story, Jason. And, yes, cross country flights rarely go exactly as planned, even relatively short cross country flights.

General question: On a ferry flight of an unfamiliar aircraft, did you actually check the oxygen supply and function before departing for your trip?

John Vesey

I definitely do a very thorough check out prior to flying an aircraft that is new to me (specific aircraft, not the make and model). I kind of have a checklist I go through, checking radios via handheld I bring with to verify transmission, vor cross check, gps system checks, a thorough preflight, long runup, usually a stop after the runup and a look through under the cowling to see if there happen to be any leaks, etc. I like to have a chat with the maintenance providers and previous owner also. And, yes, definitely, a check of the O2 system if I cam going to be using it. In this case, I checked the cannulas that were going to be used, the flow rates, quantity onboard, and the delivery of the O2 on this particular aircraft to make sure it was working prior to the flight. There is always some added risk with a flight in an aircraft you have not seen before, but I always try to mitigate as many of them as I can by being as thorough as possible. There are definitely times where I have said no, delayed to deal with issues, or needed to wait for better weather based on some systems inability to fully perform. But, in a few cases, like this one, things go off without a hitch.