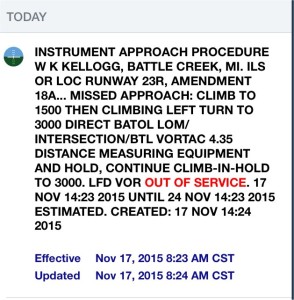

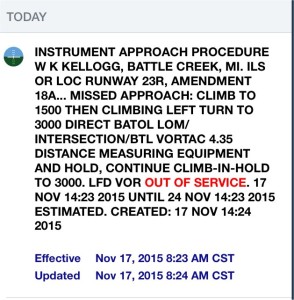

Over the past month, I have on at least 3 occasions noted prior to flights that the approaches I would normally have intended to use for my destination airport were Out of Service when I checked NOTAMs. This was able to be managed when known ahead of time, but in two of the cases it did require some re-planning to make accommodations.

Know before you go, don’t forget to check those NOTAMs for your destination and alternate airports to make sure what you are planning on flying for approaches is going to be available and won’t leave you scrambling at the last minute to try to come up with a Plan B.

NOTAMs that affect approaches can be obtained through a weather briefing both digitally and on the phone, and in most modern flight planning applications on devices such as iPad’s they are easily retrievable.

Be sure to check the details. It won’t always be the case that an approach is NOTAM’d completely out of service, but particular parts of it may be made unavailable, and depending on the type of equipment in your aircraft, it may or may not make the approach unusable by you for your flight.

Be sure to check the details. It won’t always be the case that an approach is NOTAM’d completely out of service, but particular parts of it may be made unavailable, and depending on the type of equipment in your aircraft, it may or may not make the approach unusable by you for your flight.

Many times, we find that VORs are out of service that define step-down fixes, NDBs that define outer markers may be out of service, or a glide-slope may be out of service. Each of these factors may not entirely make an approach unusable, but may change the minimums, may require that an aircraft with an IFR GPS use GPS data to supplement identification of a step-down or crossing fix, or may require use of an alternate missed approach procedure if the primary one is not able to be used.

This is much easier to think through and figure out if you are doing so prior to departure than it is if you are “in the soup” 10 miles from what you thought was going to be your final approach fix when you get the note from ATC that the approach is unavailable. Continue reading →

This past summer we were visiting friends in Bermuda and got talking about how their family came to Bermuda originally. While Martin came to Bermuda after meeting his dear wife Jo, she was born on the island and it was her grandparents that had been the first generation of her family to emigrate to Bermuda.

This past summer we were visiting friends in Bermuda and got talking about how their family came to Bermuda originally. While Martin came to Bermuda after meeting his dear wife Jo, she was born on the island and it was her grandparents that had been the first generation of her family to emigrate to Bermuda.