There is lots of other data that I (and hopefully you may) find interesting in the U.S. Civil Airman Statistics each year. Ok, I’m probably more of a data dork than most, but someone else has to join me in at least some of this, so here are a few other interesting points I just thought I would share.

No Half the People Don’t Fail the Initial CFI Test

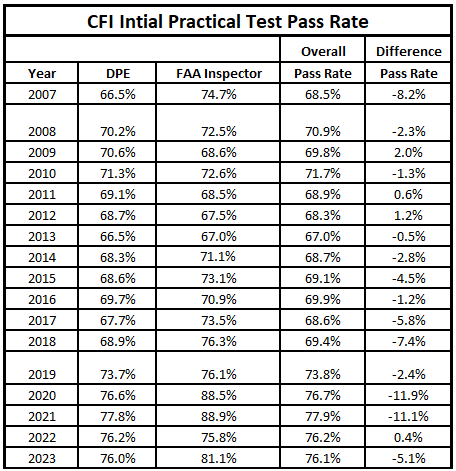

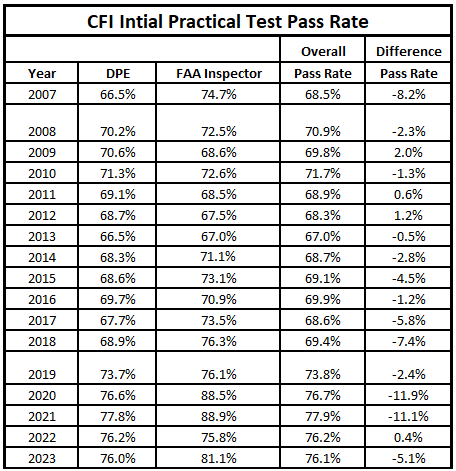

There is a long-standing myth that half the people who take their initial CFI certificate practical test fail it. There is a further myth that if you happen to be taking such a test with an FAA inspector, you are bound to fail and just should be ready to take the second attempt at some point.

The data proves different points on this topic however. In fact, the pass rate seems to have gone up over the past 15 years from around 66.5% to a whopping 76% pass rate for initial CFI certificates with DPEs last year. While FAA inspectors don’t do many of these tests, they actually tend to pass people more frequently as percentage point than DPEs do! Any column on the right of the table here that is negative is a year in which FAA inspector administrated initial CFI practical tests had a better pass rate than the ones conducted by DPEs. Of course, their sample size is much smaller.

Across the system, FAA inspectors have been averaging only about 1% of the practical tests conducted in recent years.

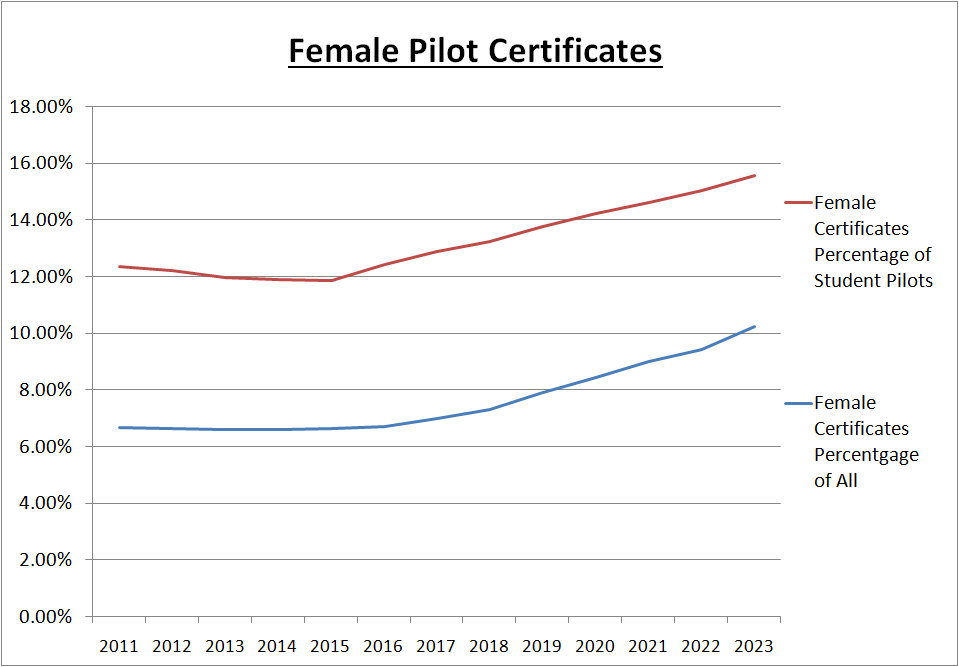

Female Pilot Certification Continues to Climb (slowly)

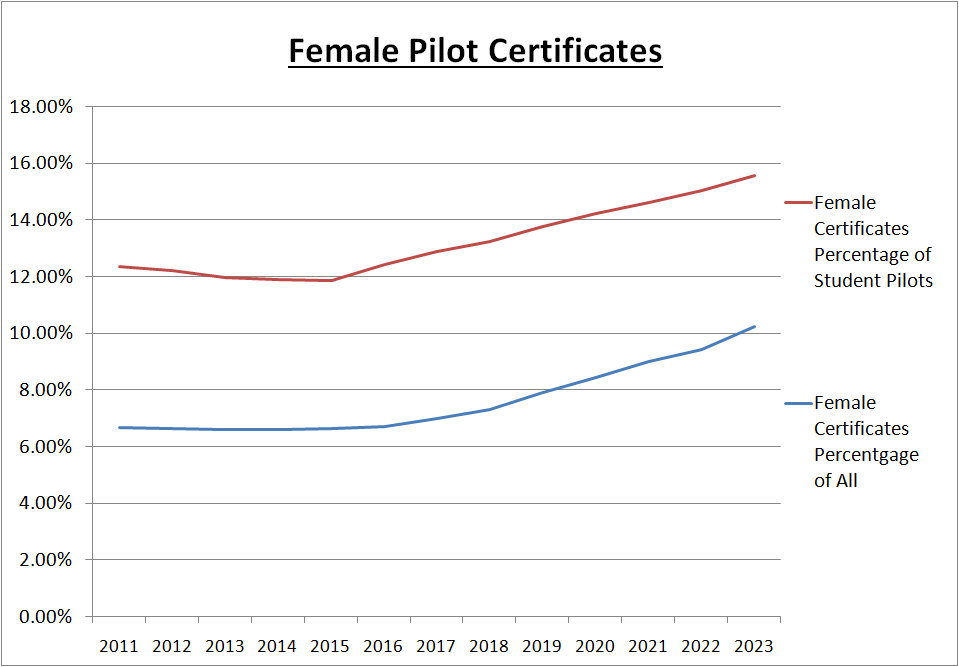

Since 2011, when there were 41,316 pilot certificates held by females, we have progressed to 2023, having 82,817 pilot certificates held by female aviators. This represents 10.26% of overall pilot certificate holders, up from 6.69%.

It’s an increase, although probably not as much as we would all like to see it be. We continue to see the certification of female aviators increase as a percentage of the overall pilot population. From a pure numbers standpoint, the increase over the past 12 years represents a little more than a doubling of certificated female aviators.

Like some of our other ratio-based considerations, as our senior pilot cadre ages out of our system, I do expect the ratio to pick up speed in its improvement due to increased female pilot certification rates in recent years compared to past decades. But we can always do better at recruiting female aviators if we want to see the balancing of male to female pilot ratio happen faster.

Building More Mechanics?

Pilots are great, but any good mechanic will tell you they are worthless without a good mechanic to keep their planes operable. They are right in lots of ways. Without mechanics, we aren’t going to be able to keep our aviation system safe or working at all.

Pilots are great, but any good mechanic will tell you they are worthless without a good mechanic to keep their planes operable. They are right in lots of ways. Without mechanics, we aren’t going to be able to keep our aviation system safe or working at all.

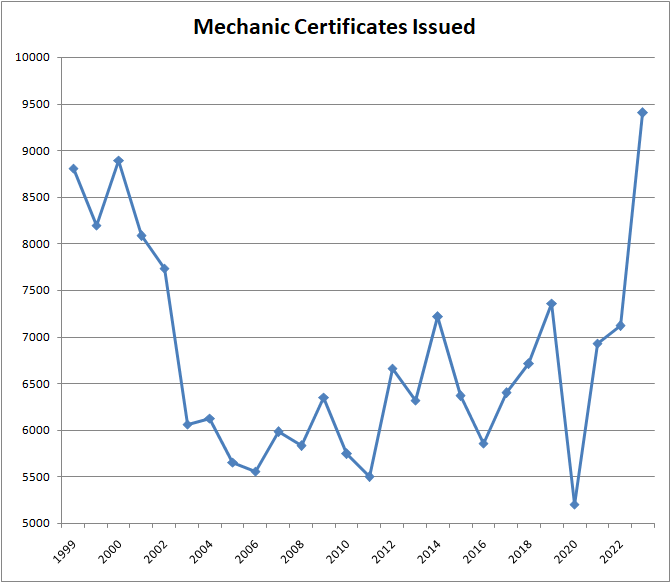

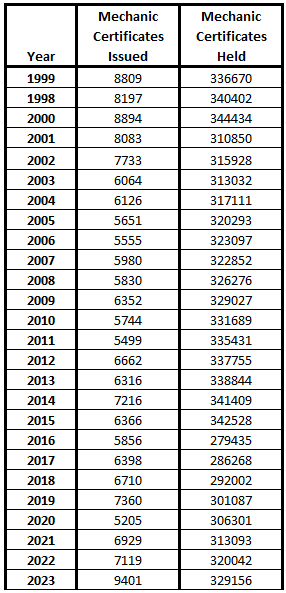

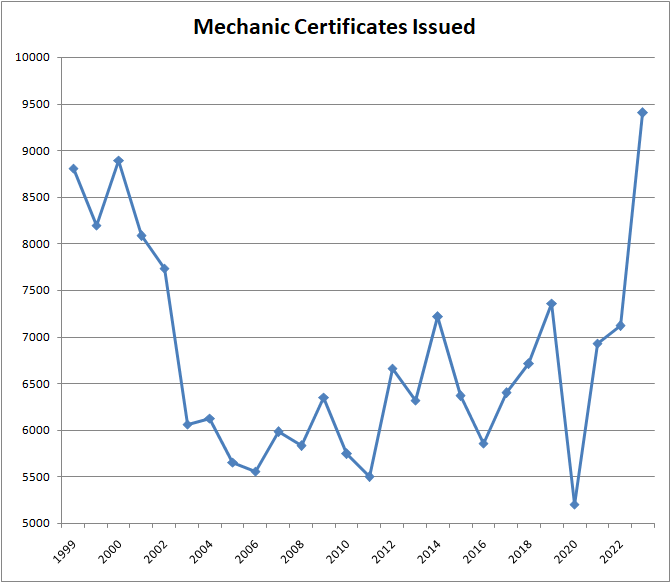

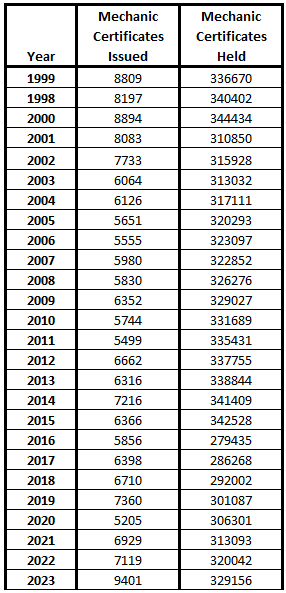

In the past couple of years we have seen some interesting trends in the mechanic realm.

Mechanic certificate numbers tend to be trending up slightly, although not at the rates we are seeing in many of the pilot certification events.

Our industry is going to need to continue to recruit individuals into the aviation maintenance career path if we are going to have a next generation of maintainers to keep our fleets of aircraft moving for training and travel service.

The aviation mechanic realm remains highly male-dominated. At the end of 2023, of the 329156 mechanic certificates held, a mere 9202 were held by females (0.9%).

It does at least appear that the trend in certification for mechanics is returning to numbers closer to what we experienced at the turn of the millennium.

Some Random Data Points

Much of the time, we focus our data endeavors on the main paths that people think about. But there are some pretty cool rabbit holes to go down, and less common sectors of aviation are just as valid, sometimes more fun, and often not thought of as frequently.

So, I thought it might be fun to include a few interesting data points at the end here.

- 71 Recreational Pilots / 7144 Sport Pilots – A rarely used certification process, there are an estimated 71 pilots in our system that are certificated only as Recreational Pilots. This certification has largely been outdated in many instances by those who become certificated only as sport pilots, of which there are 7144.

- 838 Parachute Riggers – Want your parachute to open properly? Well, you probably want a parachute rigger. At the end of 2023 there were only 838 FAA certificated Parachute Riggers in the system. Many people forget this is even an FAA certificate!

- 194,332 Flight Attendants – While they may help make your flight more comfortable on a commercial airline, their real job is safety and management of the cabin of the aircraft. At the end of 2023 we had 194,332 such FAA certificated professionals to help keep things safe and in order in our entire commercial aviation system.

- Most Pilots Have Instrument Ratings – Of the pilots who have private, commercial, or ATP certificates (excluding student, sport, and recreational pilots), 69% are estimated to have instrument ratings. Most pilots who get a private pilot certificate go on to get an instrument rating. Naturally those that are going to be operating on commercial operations commonly will need to do so.

- 368,633 Remote Pilots – A growing percentage of our certificate airman statistics, the number of remote pilot certificate holders is climbing. Of these, 30,935 are women (8.4%) One must wonder when the number of remote pilot certificate holders will surpass the certificate holders of onboard piloted aircraft? Will that day come? Also interesting on remote pilots, while it might at first thought be surmised that this would be a very young group of individuals adopting the remote pilot certification, the trend of average age for remote pilots has been approximately 42 years old.

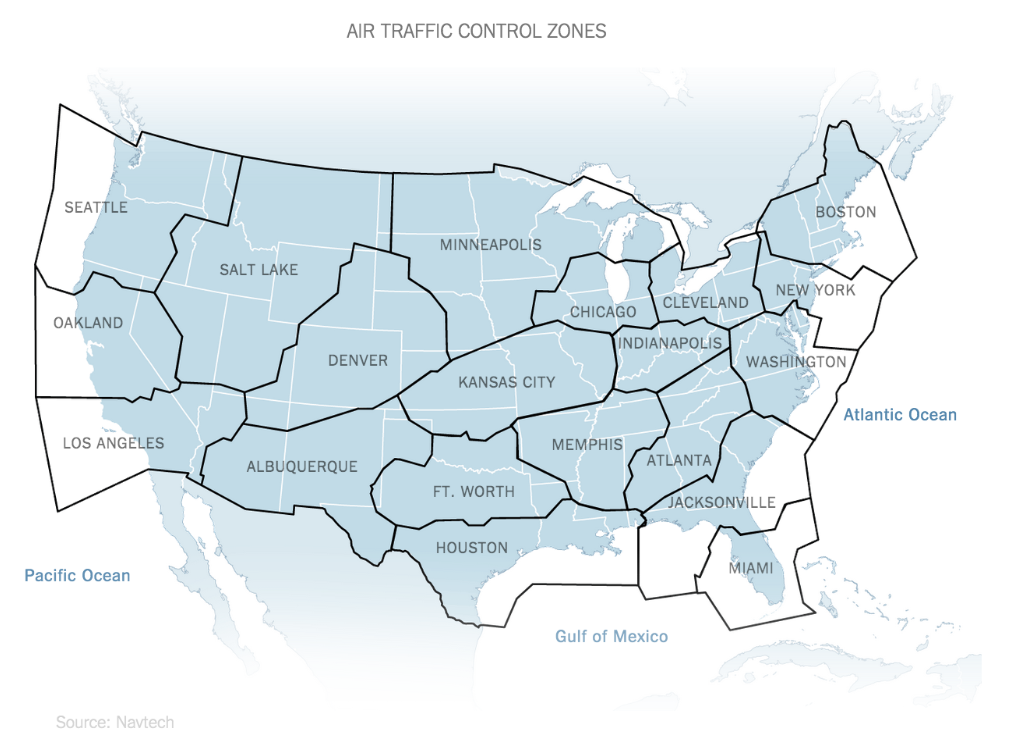

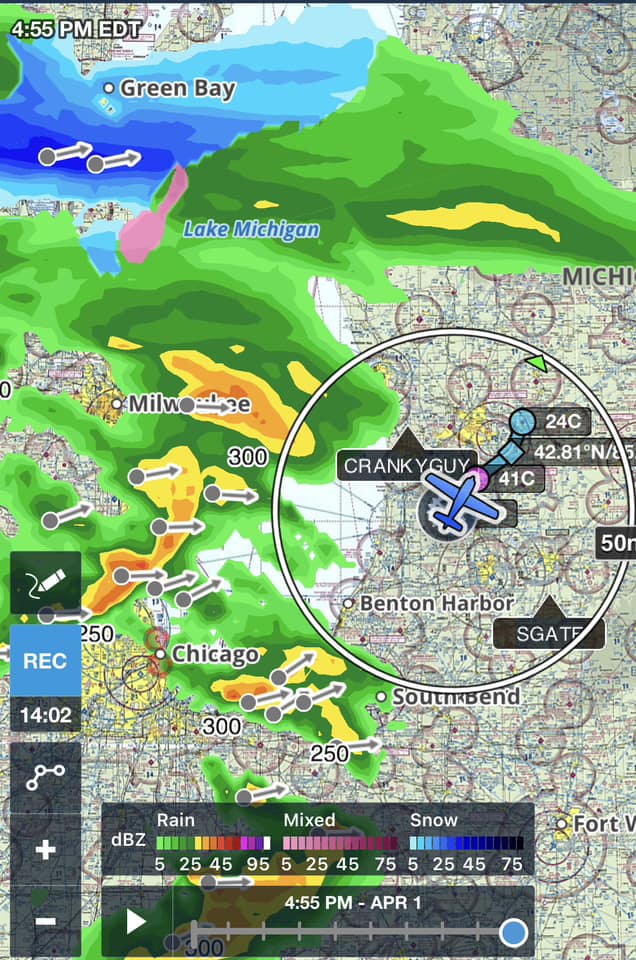

Want to get a quick big picture briefing for an area for a day? You can do this like the controllers to if you check out the Pre-Duty Wx Briefing that Center controllers get when the come on station each day.

Want to get a quick big picture briefing for an area for a day? You can do this like the controllers to if you check out the Pre-Duty Wx Briefing that Center controllers get when the come on station each day.

Pilots are great, but any good mechanic will tell you they are worthless without a good mechanic to keep their planes operable. They are right in lots of ways. Without mechanics, we aren’t going to be able to keep our aviation system safe or working at all.

Pilots are great, but any good mechanic will tell you they are worthless without a good mechanic to keep their planes operable. They are right in lots of ways. Without mechanics, we aren’t going to be able to keep our aviation system safe or working at all.